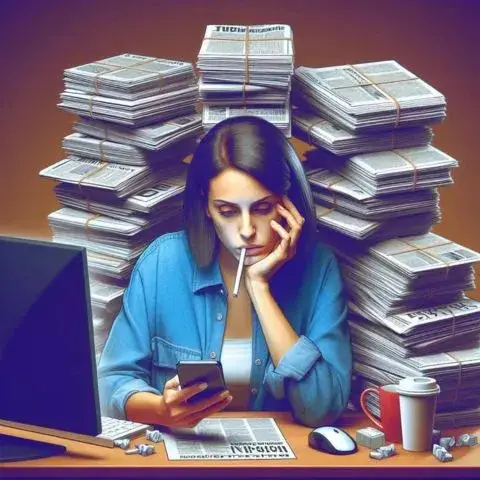

Narcotizing dysfunction is a term used to describe a situation where people become so overwhelmed by the constant stream of news and events, especially negative ones, that they become numb and stop reacting to them. This idea was introduced by social scientist Paul Lazarsfeld and his colleague Robert Merton in 1948. They observed that when individuals are bombarded with too much information, they may feel like they are doing something by simply staying informed, but in reality, they end up doing nothing to address the problems. This can lead to apathy and a lack of action, even in the face of serious social issues. In today’s world, with the rise of social media and 24-hour news cycles, narcotizing dysfunction is more relevant than ever, affecting how we respond to crises around us.

The Psychology Behind Narcotizing Dysfunction

Narcotizing dysfunction happens because of the way our minds react to constant exposure to shocking or distressing information. When people hear about tragedies, conflicts, or environmental disasters all the time, their emotional responses can become weaker over time. Initially, such news might make them feel sad, angry, or motivated to act, but as these events keep repeating, the emotional impact fades. This is called desensitization. Instead of feeling the urge to help or make a change, people start to tune out, thinking there’s nothing they can do. This lack of emotional reaction and engagement with the world around us is a key part of narcotizing dysfunction, leading to less action in society when urgent problems arise.

Causes of Narcotizing Dysfunction

The main cause of narcotizing dysfunction is the overload of information that people are exposed to daily. With the rise of the internet, social media, and 24-hour news cycles, we are constantly bombarded with news and updates, many of them negative or distressing. While staying informed is important, too much information can overwhelm our minds. Social media, with its endless updates and videos, adds to this feeling of overload. Instead of making people take action, this constant flow of news often makes them feel powerless or exhausted. People start believing that by just reading or watching the news, they are doing something, but in reality, it leads to inaction.

Effects of Narcotizing Dysfunction on Society

Narcotizing dysfunction has a significant impact on society. When people become numb to the constant stream of bad news, they lose their motivation to act or help with social issues. Problems like climate change, political corruption, or poverty often get ignored because people feel that their individual efforts won’t make a difference. This lack of engagement leads to fewer people participating in community work, protests, or voting. It also makes it harder for society to address urgent issues, as the public becomes indifferent. Overall, narcotizing dysfunction reduces the collective power of people to bring about change and solve important problems.

How Narcotizing Dysfunction Affects Individuals

On a personal level, narcotizing dysfunction can make people feel disconnected from the world. When they see so much negativity and tragedy without feeling the need to act, it can lead to emotional burnout and a sense of helplessness. People may start to avoid certain topics or news altogether because they don’t know how to cope with the overwhelming emotions. This can make them feel less involved in their communities and in the world, leading to a reduced sense of responsibility and empathy towards others. Over time, it can also affect mental health, causing stress, anxiety, and even depression.

Solutions to Combat Narcotizing Dysfunction

To fight narcotizing dysfunction, it’s important to change how we consume information. One solution is mindful media consumption—choosing to take breaks from news and social media and focusing on quality, balanced sources of information. People can also get involved in social causes, volunteering, or joining activist groups to make a tangible impact. Educating ourselves about the issues and taking small, manageable actions can help prevent feelings of helplessness. It’s also important to take care of our emotional well-being, practice empathy, and encourage others to be more engaged. By becoming more active and conscious of our responses, we can reduce the effects of narcotizing dysfunction and create a more proactive society.